Another Day in Kenya – Chapter 5

Bumpy At Best

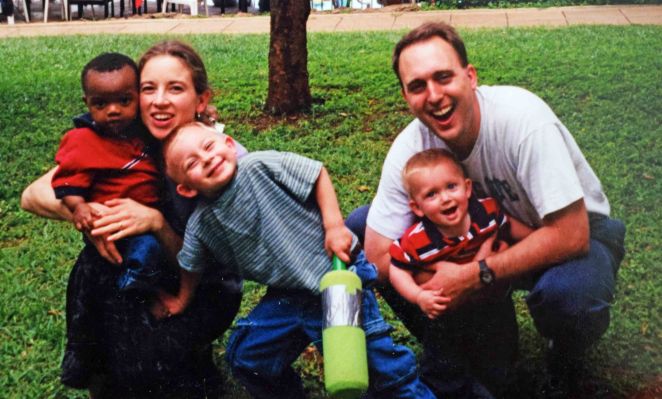

first family photo in Kenya, May 2001

Bonding with Jedd continued at a heads-over-heels pace. For the first week, if anyone else except his grandma indicated they wished to hold him, he turned his face and cuddled into my chest. For naps or bedtime, he fell asleep in my arms; and only then could I lower him into his port-a-crib. Sister Fidence told me he was literally dying for a mother’s love. In my own heart, there nestled a sense of completion, a Jedd-sized hole filled at last. After about a week, Jedd finally allowed David to hold him, and then grandpa and uncle.

Each day, Jedd emerged more and more from his wide-eyed shell. One day he clapped. All of us imitated him, erupting into laughter. An expression of confusion on his face quickly morphed into that brilliant smile that lit up his entire being. He seemed increasingly surprised and delighted to realize he could be the center of attention. Ordinary objects like ceiling fans fascinated him. Riding in the car with the window open one day, I noticed he turned and twisted away. I wondered if he ever felt wind before?

Jedd learned to wave while saying “hi”, and practiced his new skills with wild abandon as we went about Nairobi working on his Kenyan travel document and American Embassy visa. As if we were not already conspicuous, a large crowd of white people ranging in age from 12-months to grandparents, a beautiful little Kenyan baby strapped to our back greeted everyone like long-lost friends. Wherever we went, eyes openly stared at us, sizing us up, trying to figure out why we were together. Reactions ranged from warm to guarded. I wondered what they thought of us. At the same time, I realized it was only the beginning.

During our process of deciding to adopt Jedd, David and I wrestled through our own stereotypes and latent prejudices about race. We tried to anticipate the challenges we might face as a multiracial family. I drew deep strength and courage from the people closest to us, family members who anointed us with undivided support. I also knew deep down in my bones that what we were doing was the call of God. I believed without a doubt that this was His idea. And even though I, as a quiet and reserved introvert, hated drawing attention to myself, I also experienced a certain streak of rebellious satisfaction in stirring things up: challenging assumptions, forcing people ask questions and seek truth beyond the lull of status quo. I felt that if even one person understood through our story that we are all made in the image of God, all beloved of Him, the challenges of raising a black child as white parents would fade into pure joy.

Once while visiting the older children in their ward at Mother Teresa’s, caregivers were trying to serve them lunch. However, the kids were distracted by us and refused to eat. Finally, laughing, we left. My mother-in-law, a teacher, remarked to one of the sisters that the children were acting exactly as would American children in the same situation.

“Yes,” Sister Jamesina responded, “we are all God’s children. We are all alike.”

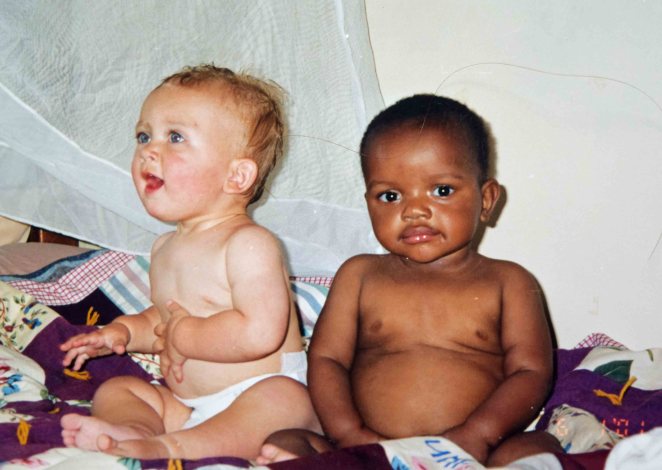

Justin and Jedd seemed thrilled to become twins. They passed toys back and forth, and babbled to one another, taking turns to listen and reply. After a few weeks, they squabbled for the first time. Justin crawled up to Jedd and indicated he wanted a water bottle in Jedd’s hands. Jedd clutched it tighter and turned away. Justin screeched in frustration, lifted his little fist, and whopped him over the head. Jedd screamed, and I scurried to separate them. At the same time, every morning, Justin crawled over to Jedd and waved in his face to welcome him to the day. Jedd refused to sleep without Justin in the same room. They enjoyed watching each other and making each other laugh.

twins: justin and jedd, June 2001

Bonding with Jedd’s birth country, however, could only be described as bumpy, at best.

About a week after our arrival in Kenya, we moved from the missionary guest house in Nairobi to Daystar University in Athi River, about an hour outside the capital city. Tim and SueAnne lived and worked there; and, miraculously, their daughter and my dear friend, Julie, and her husband would arrive in Kenya to adopt their baby soon after we moved to Daystar. As we drove out to Athi River, the openness of grasslands dotted with acacia trees, the Ngong Hills in the distance, and occasional sightings of giraffes and gazelles soothed our souls from the chaos and insecurity of the city.

Upon arriving at the gated and guarded compound of the university, we learned the dorm where we were staying was scheduled to be fumigated the next day. We lugged our bags up to our second floor rooms, slept the night, and then carried them back out the next day. The staff of the university warned us to watch our bags so they would not be stolen. SueAnne offered to let us use her electric washing machine, and we gratefully accepted. David, his brother, and his dad stayed with the kids and the bags outside the dorm building while my mother-in-law and I began the tedious process of washing eight days of eight peoples’ dirty laundry. We added water to the machine with buckets for the wash cycle, waited while the load ran, added water again for the rinse cycle, and hung the clothes on lines to dry. By the end of the day, with all the laundry hung but no sign of the fumigators, the staff told us we could move in and the fumigators would come after our departure.

The dorm conditions and surrounding creatures challenged our western standards of living. That first night, David and his brother walked to SueAnne’s house after dark to retrieve our laundry. Along the winding, rutted road, they spotted a baby snake, a large tarantula-type spider, and a huge millipede as long as a finger and as thick as a pencil. SueAnne told them she once saw a 12-foot python on that same road. Jacob liked to play on a pile of rocks until one day a passing woman asked if I was worried. Puzzled, I asked if she thought he might fall. She informed me that the rocks were home to snakes!

With no screens and warm temperatures, bugs and birds joined us freely in our rooms. A few chickens even visited. We slept under mosquito nets for protection at night. One morning Jacob’s skin ignited with little red bumps. SueAnne suggested he might have fleas in his bedding. We ironed his sheets and blankets, and the problem seemed to resolve. One morning, we went out to play and discovered ourselves in the company of a multitude of 3-inch grasshoppers, which disappeared by mid-day.

Only one of the five toilets in the communal bathroom worked, and the showers produced cold water. All our drinking water needed to be boiled. Justin, who was sick soon after our arrival, became the first domino in a rapid succession as one by one, we succumbed.

We ate in the school cafeteria. It was a beautiful walk across the campus of flowering bushes and trees, but we struggled with the food. Kitchen staff ladled soup from a huge, dented metal pot over rice or pasta. They served vegetable salads and fresh fruit occasionally; but we were afraid to eat them, fearing they were washed in un-safe water. In the mornings, the staff set out uncovered bowls of butter and jam, which were eagerly scouted by birds and cats. We learned to hurry to breakfast and guard the bowls we intended to use.

My experience of culture shock reached critical mass one day.

……………………………………………….

Dave and his brother leave early in the morning for Nairobi to work on Jedd’s Kenyan travel document. They catch the free bus service to the city, provided by the university.

My mother-in-law is very sick; SueAnne suspects a parasite.

I walk over to SueAnne’s house to email my parents. Justin and Jacob are both over-tired and grumpy. Jedd sits on the floor next to me, and soon produces a huge blow-out. His clothing is saturated. I only have a diaper with me, no extra clothing or wipes. I clean him up as best I can and load him in the baby backpack wearing just a diaper. I wrangle the other two boys, and we make our way back to the dorm.

As we approach, my father-in-law motions for us to hurry from a window. He reports David called. The photos of Jedd needed to secure the travel document are not in the correct format. David is asking me to catch the bus at 1 for town so we can take new photos. I check the time: 12:30. I grab all the supplies needed for Jedd, including food, since we will miss lunch. I change into culturally-appropriate clothing. As I rush, I notice our camcorder and camera bags are missing from the top bunk where we store them, including all film and footage taken since our arrival in Kenya. My father-in-law assures me he was nearby the entire morning and saw no one. He suggests maybe David moved the bags. He urges me to just hurry to catch the bus. I feel sick to my stomach. I know the cameras were there that morning. I race off in a fluster with Jedd strapped to my back, fighting tears.

Jedd and I sit on a rock for thirty-five minutes at the spot where people tell me to catch the bus. We are the first ones there as a large crowd gathers. At last the approaching bus kicks up a cloud of dust. I realize, horrified, that it is pulling past me to what should be the back of the line! A swarm of people stampede the little door as it creaks open. It is like a mosh pit. Several times I lose my balance and think I will fall. I realize there is no way I can push my way through with Jedd on my back. I watch, feeling completely desperate and helpless, as the bus fills to capacity. Even the aisles are stuffed with standing people. There are still 20-30 people in front of me.

I turn to the woman next to me and say, “I have to get to town!”

She replies, “I’m sorry.”

I walk away, crying. And then I really lose it. I find SueAnne, Julie and her husband, and I sputter through tears, “I can not get on the damn bus when they are pushing and shoving like that!”

I am so upset, I can’t tell them any more. I can only say I need a few minutes to collect myself.

For the next two hours, I leak tears continuously as SueAnne contacts David to alert him I won’t be arriving. They decide taking a later bus will not allow us to complete our business, and we will need to try again the next day. David confirms he did not move the cameras. Sue Anne contacts campus security, but the bags are long gone. It’s not the loss of the cameras that grieve me, it’s the loss of all the film and footage of those first days of becoming a family. We post a notice in the surrounding community, begging for the film to be returned with complete impunity, to no avail.

But unlike photos and video that can be stolen, the evidence of becoming a family is written in indelible ink in our hearts.

Later that evening, after David returns, we walk with our twins through the campus, alight with setting sun. We drink in spacious views of savanna and acacia and flowering trees. Crickets serenade with gentle cadence. We pour out our frustration and confusion to each other; and decide, as we always do, how grateful we are that no matter what, we are in this together. We talk of living in the middle of a miracle. Why us? Why Jedd? And yet here we are, halfway around the world because God gave us to one another.

We find an empty, open air chapel. David holds Justin and I hold Jedd. We whirl our twins around, spinning, laughing and dancing in the African sunset.

Colleen, I’ve been reading these chapters in your story with Jedd, and each one brings tears to my eyes. Wow! Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading Joanna, and for taking the time to encourage me! It really helps me to keep going to know that it’s connecting with people. I don’t think I could stay motivated, writing in a vacuum! Good thing I live in the internet age.

LikeLike